Context Engineering as the New Security Firewall

Youssef Harkati(BrightOnLABS) (Author)

Ken Huang (Distributedapps.AI) (Author)

Edward Lee (JPMorgan Chase & Co.) (Reviewer)

As organizations move from simple chat-based LLMs to agentic workflows (systems that retrieve documents, keep memory, and invoke tools), the key security boundary stops being “the network perimeter” and becomes the context window. An attacker doesn’t have to break the model itself, they can often win by influencing what the agent reads (a web page, a ticket description, a PDF, a tool response) and thereby steering the model’s working memory. This is exactly what indirect prompt injections are, where external content can hijack behavior and lead to data exposure or unintended actions.

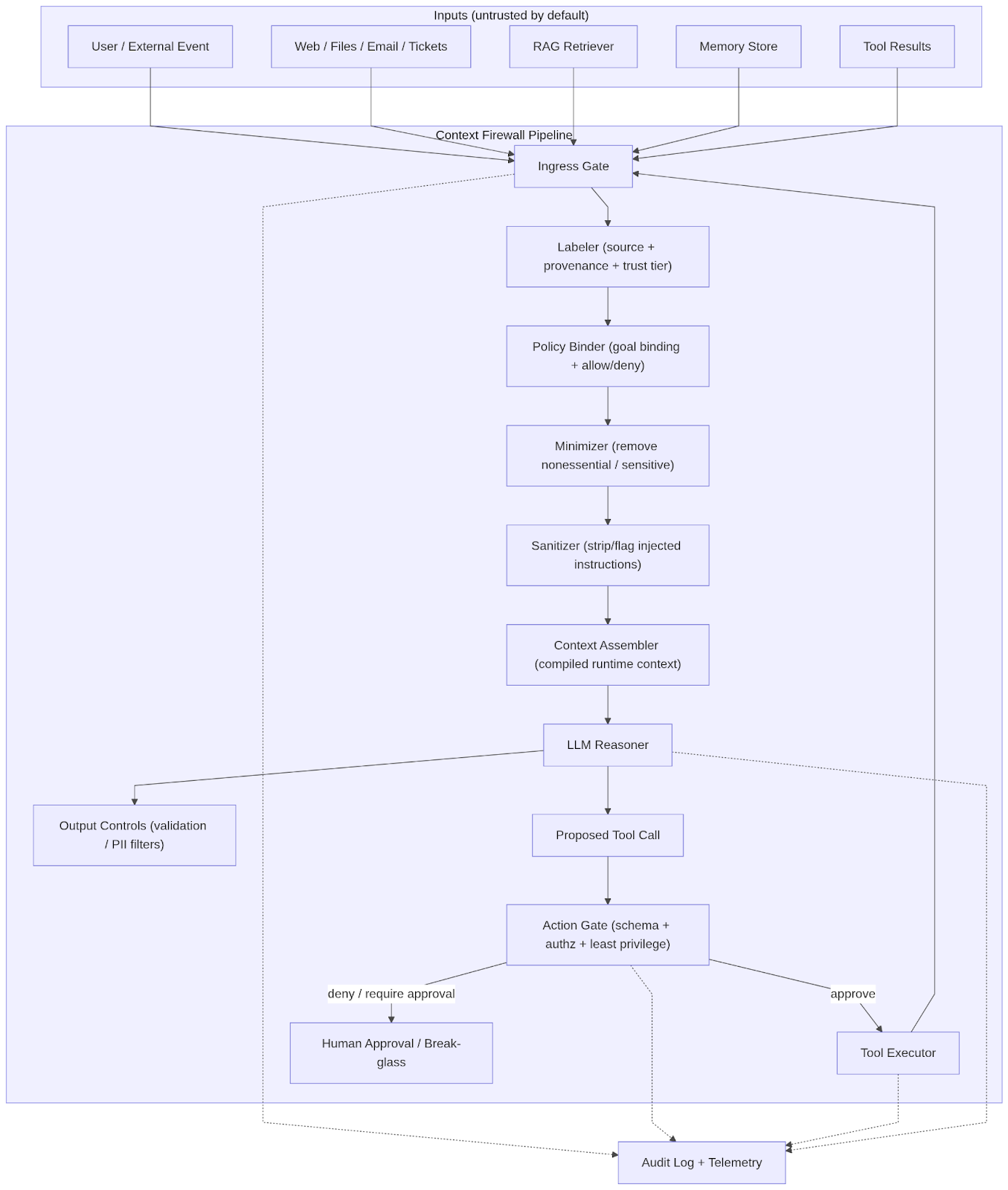

In this blog post, we treat context engineering not as a productivity tool (which is very popular nowadays) but as a security control. We introduce a “Context Firewall” architecture: a multi-stage pipeline that assumes inputs are untrusted by default, binds context to trusted goals and provenance, minimizes and sanitizes tool I/O, gates high-impact actions, and produces auditable “compiled context” artifacts. This shifts the defensive focus from “filter the final answer” to “governing the full information lifecycle” across the agent’s perception and action loop, consistent with the defense-in-depth approach, like described by Microsoft for indirect prompt injection.

1. Introduction

Traditional security assumes deterministic software boundaries: APIs, schemas, authorization checks, and network controls. Agentic AI breaks this assumption because the control plane becomes language. The LLM “decides” what is instruction vs. data, what is relevant, and what action to take, based on tokens in its context window.

A useful security mental model is:

LLM = probabilistic CPU (unlike a real CPU, an LLM’s decisions are probabilistic, not deterministic)

Context window = RAM (volatile working memory)

Durable storage = KBs / vector DB / logs / docs

Tool calls / MCP = system calls

Context engineering = memory manager + security monitor

This analogy is a good way to explain why context engineering is more than prompt tuning: it is the discipline that governs what is loaded into the agent’s “RAM”, and therefore what the agent can “think” and do.

2. Context Engineering VS Prompt Engineering

To properly secure these systems, it is necessary to distinguish between prompt engineering and context engineering. Prompt engineering is primarily focused on the linguistic optimization of phrasing to improve the accuracy or tone of a model’s output. Prompt engineering optimizes phrasing. Context engineering, by contrast, is an architectural discipline focused on the continuous curation and governance of the entire inference payload. This includes the management of system policies, task specifications, few-shot examples, retrieved passages, tool schemas, memory slices, and environmental states

The context window is a constrained resource, and effective systems depend on selecting the right context, not the most context.

A production-ready definition that aligns with agent systems, could be: context engineering is the continuous curation of the information environment around an LLM throughout execution, including allocation policies, compression, retrieval triggers, and memory tiers.

3. Threat Model: Context as the Primary Trust Boundary

Agentic systems are composed systems: they ingest data from multiple sources (user inputs, files, web, RAG, memory, tool outputs) and then use an LLM to decide what to do next. The core security problem, is that most implementations flatten these heterogeneous sources into a single token stream, and LLMs do not reliably enforce a hard boundary between “instructions” and “data”. Indirect prompt injection happens when models accept input from external sources like websites or files, where embedded content can alter behavior in unintended ways.

This section models the context supply chain as the new trust boundary: the attacker targets what enters the context window and how it is interpreted, rather than “breaking the model.”

We assume an agent with the following loop:

Perception: ingest user request + external content like an email, a web page, etc.

Augmentation: retrieve from RAG + memory + tool outputs.

Reasoning: LLM chooses the next step (a response and/or tool call(s))

Action: tools execute under some identity/permissions.

Feedback: tool results re-enter context; memory may be updated

The goal of the attacker is to influence the agent’s decisions and/or actions by controlling one or more context sources, and often, does not need direct access to the user prompt interface.

3.1 Indirect Prompt Injection (IPI)

IPIs occur when an LLM ingests external content (websites, files, database fields, tickets, emails) that contains malicious instructions, which the model treats as if they were authoritative directions. Why does it matter more in agents than chatbots ? In agentic workflows, external content isn’t “background”; it is often directly inserted into the model’s working memory to support decisions. Microsoft describes this as a scenario where the model misinterprets data as instructions, with impacts ranging from data exfiltration to unintended actions.

A typical IPI pattern could be an attacker that plants instruction-like content in a location the agent will read (a document, a webpage, etc), and the agent ingests it as context. Then the model follows the injected instruction because it appears relevant to the response. Here is a simple demo repository.

3.2 Tool / function-call abuse

In agentic systems, the highest-risk outcome is rarely the model providing a wrong response, but it’s that the model invokes tools based on compromised context. That transforms prompt injection into an action injection. A compromised decision becomes a real-world effect.

In that sense, we must separately secure text output vs tool execution. To a certain extent, a system can tolerate some non-harmful hallucinated text, but it cannot tolerate hallucinated or coerced actions.

3.3 Context poisoning via RAG and memory

RAG and memory turn context into a distributed supply chain: the model’s “working memory” is assembled from sources that can drift, be poisoned, or persist across time. RAG and memory require write-policy controls, provenance labeling, TTL + eviction, and explicit separation between facts, instructions, and rules.

3.4 Prompt-only defenses don’t work

Many teams start by strengthening the system prompt. This is helpful but insufficient as a primary control. Why? As said above, models mix instructions and data in a single natural language stream. The transformer self-attention mechanism can easily lead to hijacked “intents”. In practice, that means an attacker doesn’t need to break the model, he just slips instruction-like content into something the agent will ingest.

This is also why transformer self-attention is a security concern: the model dynamically amplifies tokens it finds relevant, so injected or misleading tokens can become decision-driving signals and effectively hijack intent. The CSA article introducing R.A.I.L.G.U.A.R.D. frames a practical response to that reality: make code generation more context-aware by attaching explicit, enforceable constraints (Cursor Rules). In this Medium article, we go further into this “insecurity by context” problem R.A.I.L.G.U.A.R.D. is trying to address, where self-attention can elevate untrusted tokens into decision-driving signals.

4. The Security Thesis: Context Engineering as a Firewall

A network firewall governs packets crossing trust boundaries. It exists because systems must process untrusted inputs that cross these trust boundaries. A context firewall governs tokens crossing trust boundaries. Agentic AI creates a new boundary: the runtime context window. Modern LLM applications concatenate system instructions, user requests, retrieved passages, tool schemas, and tool outputs into a single token stream, and yet current LLMs do not enforce a security boundary between “instructions” and “data” inside a prompt.

Context engineering is not only an optimization discipline, it is a security control surface. In the same way a network firewall governs packets crossing networks, a context firewall governs tokens crossing trust boundaries, deciding what is allowed into the model’s working memory, in what form, with what provenance, and under what action constraints. This article from Microsoft explains their IPI defense approach with the “defense-in-depth”, which uses both probabilistic and deterministic layers.

A context firewall must guarantee zero-trust ingestion, treating all external text and tools as untrusted by default. It must maintain explicit source boundaries so models can distinguish them rather than flattening them. This defense is called ‘spotlighting’ by Microsoft. Finally, for audits and investigations, the system must record what was admitted, transformed, and why.

5. Context Firewall Architecture

5.1 Key pipeline stages

Zero-trust ingress: We must treat every inbound text blob (including tool output) as untrusted. This aligns with Microsoft’s emphasis that indirect prompt injection targets systems that process untrusted data through an LLM.

Provenance + goal binding: It binds runtime context to user intent, approved task goals, and trusted sources.

Minimization and token governance: Minimization is both security and reliability. It reduces exfiltration surface and reduces attention noise.

Sanitization: It filters retrieved content and tool responses to strip or mask instruction-like payloads.

Action gate (tool/function-call safety): It separates “final answer safety” from “tool execution safety.” In agentic systems, the most dangerous failure is often an unsafe action, not unsafe text.

Observability as a control: It treats context compilation like a governed build step. It logs what entered the context, why it was allowed, and what executed, then feeds it into monitoring/response workflows.

6. Security Design Patterns for Context Firewalls

A “Context Firewall” only becomes real in production when it’s expressed as repeatable patterns you can apply to every agent workflow. The patterns below, map directly to the dominant failure modes (indirect prompt injection, tool abuse, poisoned retrieval, and prompt-only controls) and align with Microsoft guidance on treating untrusted inputs explicitly and layering deterministic controls around the LLM..

6.1 Zero-trust context ingress + trust tiers

The idea is to treat every inbound context source as untrusted-by-default (user messages, web pages, tickets, retrieved docs, API/tool responses) and label it with a trust tier before it can influence reasoning. We must treat external data as untrusted and sanitize it before placing it into the agent context. It helps mitigate IPI and avoid the data becoming instructions.

6.2 Boundary enforcement (“instructions” vs “data”) + Spotlighting

We make the instruction/data boundary “machine-enforceable” rather than “implied” by the prompt. Microsoft calls out Spotlighting as a preventative technique to isolate untrusted inputs so models can better distinguish them from trusted instructions.

Untrusted contents are wrapped into clearly delimited segments with explicit labeling, and we route them through a dedicated quarantine step before merging into the main compiled context.

6.3 Minimize + Sanitize at the tool boundary

The tool inputs & outputs must be filtered with the help of deterministic filters. We minimize the inputs by removing non-essential and/or sensitive fields, and we sanitize the outputs by stripping and transforming the tool responses before they re-enter in the context. We avoid data exfiltration via tool calls, prompt injections from tool outputs, and accidental leakage of secret/PII through oversized tool arguments.

6.4 Deterministic tool validation + least privilege (“action gate”)

Because agentic risk is concentrated at action boundaries, a context firewall must include an action gate that separates “final answer safety” from “tool execution safety.” Minimum controls at the action gate include allowlisting specific tools per task, validating parameters against strict schemas (types, ranges, enums), and performing policy checks for secrets or restricted actions. For high-risk operations, such as financial transactions or destructive file commands, the firewall should implement a “human-in-the-loop” or “break-glass” mechanism, where a human operator must explicitly approve the agent’s proposed action.

Minimum checklist:

- Allowlist tools per task and per identity (least privilege)

- Schema validation (types, range, enums)

- Policy checks (DLP, PII, restricted actions)

- Rate limiting + anomaly detection for “agent behavior”

- “Dry run” for high-impact operations

- Human approval / break-glass for high-impact paths

6.5 Memory compartmentalization

Memory, from a human standpoint, allows us to use the brain to store and retrieve data when we need it. Memory, from an agent’s perspective, is the ability to “remember” information during an interaction. This enables an AI agent to learn and adapt itself to the user it interacts with. It is what we call “persistence”. But it is security critical to understanding the different kinds of memory in agentic systems, to control the persistence.

In agentic systems, memory is not just a UX feature, it’s a persistence layer for influence. If an attacker can get malicious content stored and later replayed into the context window, you’ve effectively turned a one-shot indirect prompt injection into a durable “memory poisoning”.

A practical way to avoid that is to stop treating “memory” as one bucket, and instead split it into tiers with different rules, because not all “memory” is equally dangerous. The 3 levels of difficulty,in the KDnuggets article are actually a good mental model. It explains the need for separating memory into tiers:

- Working memory is the context window, what the model sees at the time of processing. Anything that lands here, can steer immediate decisions.

- Long-term memory is the AI’s record of events and experiences. It helps the agent to recall past actions or interactions, learning from them.This tier of memory helps the AI to adjust its behavior.

- Semantic memory is the knowledge base, the facts, and the context that it uses for new situations. This requires provenance, retrieval hygiene, and integrity controls, because poisoned facts are hard to notice once they become normal context.

- Procedural memory is the “how to operate” knowledge. It is often embedded in its code, or fine-tuned via training. For example, the agent that learns to optimize a workflow, relies on procedural memory to run it effectively. It is a sensitive tier, because if an attacker can write instructions into the procedural memory, it is basically rewriting the operating system of the agent.

The security policy becomes simple: the more “instruction-like” a memory tier is, the harder it should be to write to it. Concretely, OWASP’s AI Agent Security Cheat Sheet gives a clean baseline for what “secure memory” needs in production: validate and sanitize before storing, isolate memory between users/sessions, set expiration and size limits, audit memory for sensitive data before persistence, and use cryptographic integrity checks for long-term memory.

Here’s how that translates into day-to-day design decisions:

Gating before persisting. Don’t let the agent just save anything. Treat memory writes like an API: validate the payload, sanitize it, and classify it (fact vs event vs preference vs instruction). If it reads like an instruction, it should not be allowed to become long-term procedure unless it came from a trusted policy source.

Strong isolation boundaries. Memory should be partitioned by tenant/user/session and by workflow. We must have a clear isolation between users/sessions; without it, you get cross-user contamination and “shared poisoning” risks.

Expiration & size limits. Memory that never expires becomes a liability. Use TTLs for episodic entries, cap how much you retain, and make eviction predictable. Those limits are what keep “persistence” from turning into long-term risk.

Audit what you store. Before anything becomes persistent, scan it for secrets/PII and policy violations, and only persist with what passes those checks.

Integrity checks for long-term tiers. For semantic/procedural stores, add integrity verification (hashing/signing) so you can detect tampering and silent drift over time.

To make this concrete, a memory layer like Cognee is a good example of how you can operationalize compartmentalized memory in an agent system. It joins different types of storage systems, each one playing a different role for handling different aspects of “memory”. Its architecture explicitly splits storage responsibility across a relational store for document metadata and provenance, a vector store for related text (embeddings), and a graph store for the knowledge part.

In a “Context Firewall” design, Cognee offers the possibility to track where memory came from, to attach trust-tier labels, and to enforce the retrieval part by combining semantic similarity and structural constraints (graph). On top of that, it offers isolation for each dataset, as it creates a knowledge graph and a vector store, per dataset.

7. Measuring Security and Reliability

If we don’t measure, we end up feeling secure because the agent “sounds” cautious, until it quietly takes a bad action. The point of a Context Firewall is to make security observable and testable, so you can quantify two things at the same time:

Did we reduce compromise?

Did we preserve usefulness?

That “security/utility trade-off” framing is exactly how modern prompt-injection benchmarks evaluate defenses.

7.1 The core metrics: BU, UA, ASR

Most serious agent-injection evaluations converge on three headline metrics:

Benign Utility (BU): how often the agent completes the user task when there is no attack. It must remain high.

Utility Under Attack (UA): how often the agent still completes the legitimate user task while resisting attacker goals in attacked scenarios.

Attack Success Rate (ASR): % of tasks where the agent follows injected instructions (target 0% in benchmark tests).

BU, UA, and ASR, alongside the usual KPI MTTD / MTTR and false positive rate.

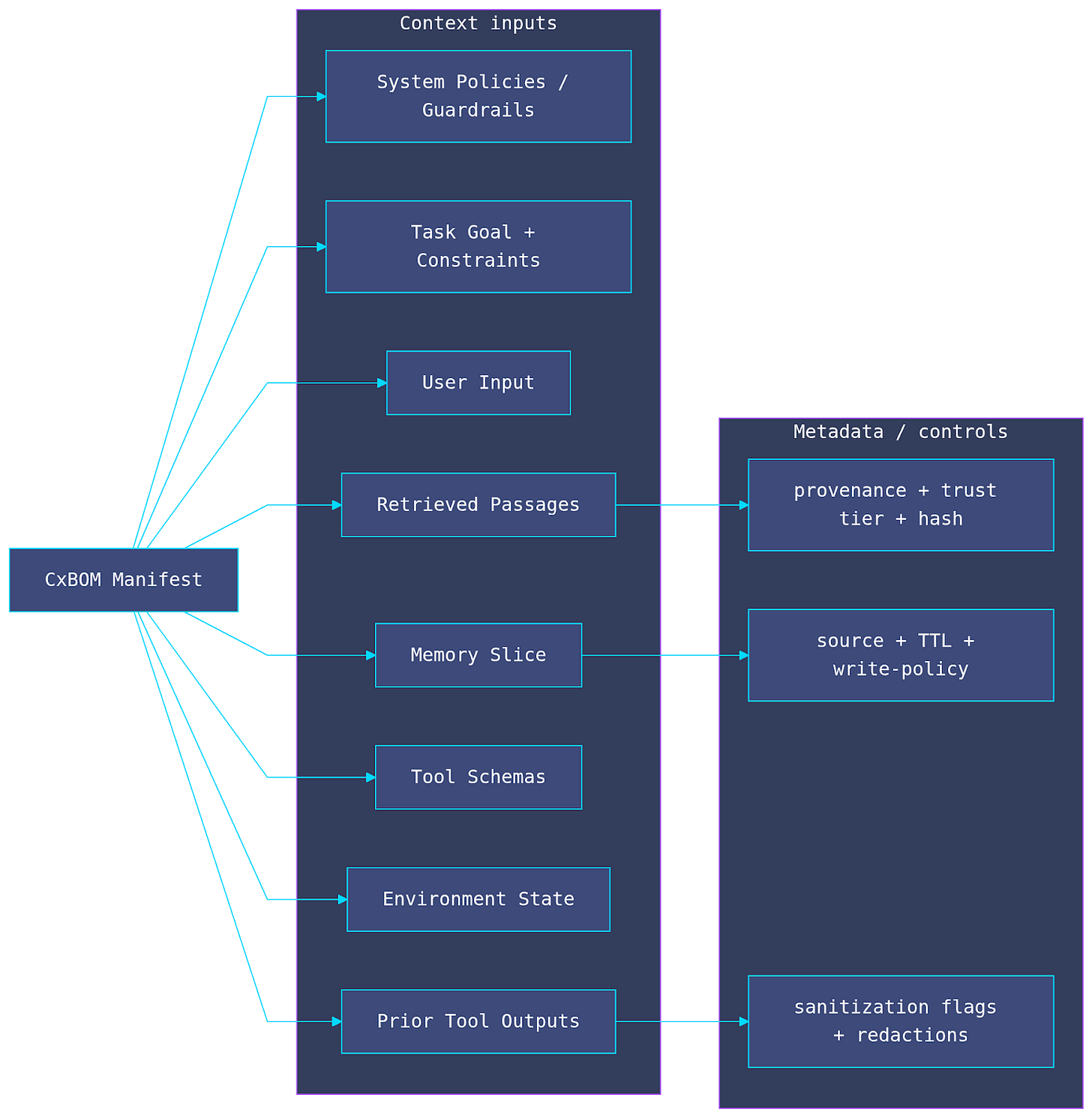

8. CxBOM: Context Bill of Materials

As organizations integrate more third-party data and tools into their AI systems, the software supply chain becomes increasingly complex. That’s the reason why I thought about CxBOM. A CxBOM is a comprehensive, structured record of all components used to construct the context window of a large language model (LLM) at the moment of inference. Unlike a static software inventory, a CxBOM captures the dynamic assembly of system instructions, retrieved data (RAG), user inputs, and tool definitions that define an AI agent’s behavior for a specific task.

Nowadays, code is no longer “the logic.” What I mean by that, is, in traditional software, the logic lives in the compiled code. In our GenAI era, the logic lives in the context. An SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) tells you which library versions are running. But the SBOM cannot tell you if the model was instructed to “ignore all safety protocols” or if it retrieved a poisoned document from the vector database.

A quick example of a minimal CxBOM schema

{

“run_id”: “2026-01-07_stepXXXXX”,

“created_at”: “2026-01-07”,

“model”: { “name”: “gpt-5.2”, “provider”: “openai”, “temperature”: 0.2 },

“goal”: {

“task”: “Assess CVE applicability”,

“constraints”: [”no secrets”, “no outbound email”, “cite sources”],

“system_prompt_hash”: “sha256:8f4b...”,

“policy_version”: “a2as_policy_v1.4.2”

},

“a2as”: {

“basic_model”: “BASIC”,

“behavior_certificate_id”: “bcert:XXXXX:vX”,

“authenticated_prompt”: {

“prompt_hash”: “sha256:...”,

“verified”: true

},

“security_boundaries”: {

“enabled”: true,

“tag_scheme”: “a2as:<source>:<id>”

},

“in_context_defense”: {

“policy_id”: “a2as:defense:prompt-injection:v1”,

“verdict”: “masked”,

“signals”: [”instruction_override”, “tool_coercion”]

},

“codified_policies”: [

{ “policy_id”: “a2as:policy:tool-allowlist:v1” },

{ “policy_id”: “a2as:policy:untrusted-ratio-threshold:v1” }

]

},

“composition”: {

“max_tokens”: 8192,

“total_tokens”: 4060,

“trusted_ratio”: 0.85,

“untrusted_ratio”: 0.15

},

“context_items”: [

{

“id”: “rag_0042”,

“type”: “retrieved_doc”,

“uri”: “kb://vuln/playbooks/cve-triage.md”,

“trust_tier”: “trusted”,

“hash”: “sha256:...”,

“tokens”: 620,

“retrieval_score”: 0.89,

“boundary_tag”: “a2as:rag:rag_0042”,

“sanitization”: { “status”: “clean” }

},

{

“id”: “web_0007”,

“type”: “untrusted_content”,

“uri”: “https://example.com/post”,

“trust_tier”: “untrusted”,

“hash”: “sha256:...”,

“tokens”: 410,

“boundary_tag”: “a2as:web:web_0007”,

“sanitization”: {

“status”: “masked”,

“reason”: “instruction-like payload”

}

}

],

“action_gate”: {

“allowed_tools”: [”vuln_db_lookup”, “asset_inventory_search”],

“denied_tools”: [”email_send”, “file_delete”]

}

}

CxBOM as a forensic snapshot. Unlike standard logs that record events, a CxBOM records the exact state presented to the model: what entered the context window, its provenance and trust tier, what sanitization fired, and which actions were allowed or denied. In this example schema, web_0007 is both untrusted and masked due to instruction-like payloads; the manifest explains why downstream behavior and tool permissions were constrained.

For example, we could use CxBOM for incident response & forensics. That would help to answer the question, “What did the model see?”. If an agent leaked data or executed a bad tool call, the CxBOM lets you trace which untrusted chunk (web page, ticket text, RAG passage, tool output) entered context and whether sanitization/policy gates fired.

9. Conclusion

Agentic AI changes the security game because the critical boundary is no longer only the network perimeter or an API gateway, it’s the runtime context that drives the agent’s decisions and actions. When agents ingest untrusted external content (web pages, documents, tickets, tool outputs), attackers can often succeed by shaping what the model reads rather than “breaking the model”.

This paper’s thesis is simple: context engineering is a security control, not just an optimization technique. A Context Firewall operationalizes that control as a governed, auditable pipeline that defends the agent’s perception/action loop with defense-in-depth, consistent with Microsoft’s approach to indirect prompt injection.

If enterprises want AI agents in production, they need to treat context construction as a security perimeter. The Context Firewall, is an idea among others, as an industry-standard layer for trustworthy agentic workflows.

10. References

- Cloud Security Alliance: Secure Vibe Coding. (CSA)

- Microsoft MSRC: Defending against indirect prompt injection. (Microsoft)

- KDnuggets (Jan 2026): Context Engineering in 3 levels. (KDnuggets)

- Elastic: Context engineering overview + context window limits. (Elastic)

- “Everything is Context” (arXiv:2512.05470). (arXiv)

- “MemTrust” (arXiv:2601.07004v1). (arXiv)

- “Prompt Injection Firewalls Are Not Secure…” (arXiv:2510.05244). (arXiv)

- Secure Reasoning. (BrightOnLABS). (Medium)

Correct, context engineering is the missing security layer. But in banking, "governed pipeline" isn't enough.

When agents interpret context as authorization for financial transactions, you need immutable audit trails proving: what context was retrieved, who controlled those sources, how interpretation mapped to authorization.