The Three-Plane IAM Stack for Agentic AI—and Where Today’s Products Fit

By Ken Huang, Apurva Davé, Dan Kaplan

Agentic AI has a way of turning old identity debates into the wrong question.

For years, security teams could argue about whether an automated system should be treated as “human” or “non-human.” Agentic workflows break that binary. A modern agent is usually both: it’s a workload running somewhere, but it often acts on behalf of a human, and it needs guardrails that are tighter than either identity alone.

The right mental model, then, isn’t a binary identity at all—it’s a blended (hybrid) identity. In practice, an agent carries two truths at once: it must authenticate as a machine workload (because it runs autonomously at machine speed), while it must act under a delegated human context (because a user initiated intent and remains accountable). The security requirement that falls out of this is straightforward but non-negotiable: delegation must be constrained, meaning the agent should operate with a down-scoped subset of privileges that matches the specific task, not the user’s full reach.

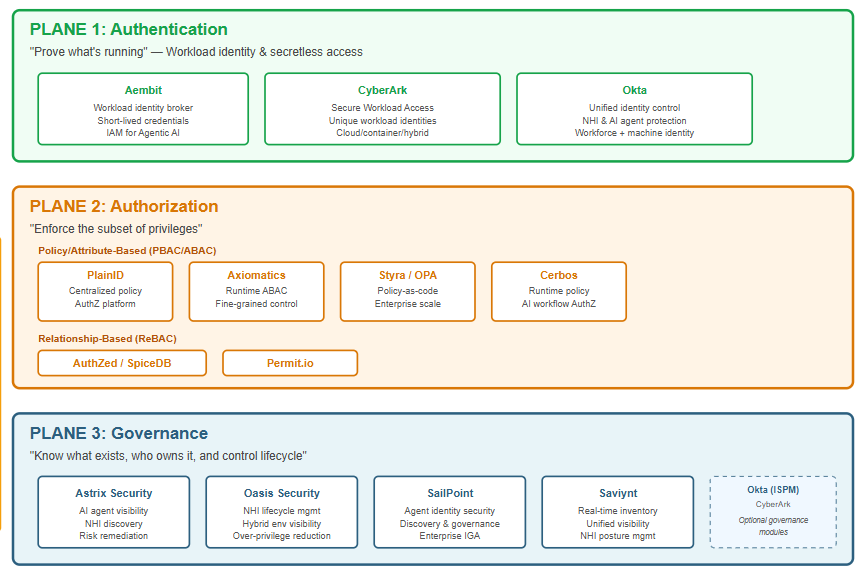

Once you accept that agentic AI is fundamentally a hybrid identity problem, the cleanest way to reason about the market isn’t “human vs. machine.” It’s a three-plane stack:

Authentication (AuthN): Who/what is this agent process, right now?

Authorization (AuthZ): What is this agent allowed to do, in this specific context?

Governance: What agents and non-human identities exist, who owns them, and how do we control their lifecycle?

Vendors will often claim they “do it all,” but most products have a natural home plane—and understanding that mapping is how you build a coherent architecture instead of a pile of overlapping tools.

Below is a practical way to place the products you listed into these three planes, written the way you’d explain it to a security leader or architect trying to build a real program.

Plane 1: Authentication — “Prove what’s running”

The first job is to identify the agent as a workload and give it short-lived credentials appropriate for machine speed. This plane is about eliminating static secrets and anchoring trust in something that can be verified continuously.

Aembit is easiest to understand as a workload/agent identity broker. Their positioning is explicitly about “IAM for Agentic AI,” emphasizing secretless access and policy control over how workloads obtain credentials. Their own materials describe replacing long-lived access secrets with short-lived credentials and limiting access dynamically based on criteria like resource and context. (Aembit)

CyberArk lands in this plane through its push into Secure Workload Access, framed as assigning each workload a unique identity and enabling secure access across cloud, containers, and hybrid environments. That’s an AuthN story first: authenticate the workload, stop credential sprawl, and avoid exposing static secrets. (CyberArk)

Okta historically dominates human workforce identity, but its NHI narrative brings it into this plane as well—especially where organizations want a unified identity control layer. Okta’s own “protect non-human identities” positioning explicitly includes AI agents and other machine identities in scope. (Okta)

One important nuance: both CyberArk and Okta increasingly blend “authentication” and “visibility” messaging. That’s not wrong—workload authentication programs inevitably run into discovery and lifecycle questions—but it helps to remember the primary control they deliver is establishing and brokering trusted access.

Plane 2: Authorization — “Enforce the subset of privileges”

This is the plane that becomes existential in agentic systems.

In classic delegated access, a system might simply “inherit the user’s permissions.” In agentic workflows, that’s how you get the disaster story: a user has broad access, the agent is tricked by indirect prompt injection or a bad tool invocation, and suddenly the agent uses legitimate credentials to do illegitimate things.

Authorization for agents must be task-scoped and down-scoped—a subset of privileges aligned to intent.

This plane breaks into two dominant patterns: policy/attribute-based decisioning and relationship-based permissions.

Policy engines and attribute/policy-based authorization

Aembit’s core capability is on Plane 1, with the advent of Agentic AI and MCP servers, Aembit is enforcing fine grained access control on MCP tool invocation. This is a good trend to watch and placed Aembit as new newcomer in Plane 2 as policy/attributed-based decision for access control.

In Figure 1 below, the Aembit MCP Identity Gateway intercepts agent requests for tools or services, creating a “blended identity” by identifying the calling agent and determining if a human user is involved, then validating that user through the organization’s identity provider. The gateway consults Aembit’s Cloud control plane to evaluate policies that define which agents can access which services and under what conditions, and if approved, performs a token exchange to obtain short-lived credentials valid only for the specific service and scope rather than giving the agent long-lived secrets. The gateway then calls the target MCP server with these ephemeral credentials, ensuring the service receives valid credentials reflecting an approved identity without exposing internal secrets to the agent, while every step is logged for a complete audit trail linking service access back to the agent and human user when applicable.

Figure 1: A high-level view of IAM for Agents & Workloads with Aembit. MCP Gateway is optional depending on use case

PlainID’s platform focuses on centralized policy discovery, management, and authorization—i.e., “authorization as a thing you operate,” not a set of hardcoded checks buried inside apps. (PlainID)

Axiomatics is one of the canonical ABAC players, explicitly positioning as a runtime, fine-grained authorization provider delivered through attribute-based controls and policy. (Axiomatics)

Styra / OPA fits this plane as “policy-as-code at enterprise scale.” The core OPA framing is decoupling policy decisions from applications so you can manage authorization consistently across systems. Styra’s enterprise narrative builds on that to support operational scale and lifecycle management for policy. (Styra)

Cerbos also sits also in Plane 2. Their headline positioning is runtime, externalized, policy-based authorization for applications and AI workflows—exactly the kind of fine-grained enforcement agents need when you’re trying to express “this action is allowed only in this context.” (Cerbos)

Relationship-based authorization (ReBAC)

Some problems are less about “attributes” and more about “who is related to what.” That’s where ReBAC shines—especially for document access, multi-tenant SaaS, and resource sharing models.

AuthZed / SpiceDB is one of the clearest examples: SpiceDB is explicitly positioned as a Zanzibar-inspired relationship-based permissions system—very good at answering “does subject S have permission P on resource R?” at scale. (AuthZed)

Permit.io is also in this camp, positioning ReBAC as easier to implement and manage, with a focus on making relationship-based policy authoring approachable. (permit.io)

In practice, many mature agent deployments combine both worlds: ReBAC to determine whether a relationship path exists (“this agent is allowed to act within this project”), and ABAC/PBAC to enforce contextual constraints (“only read these fields, only for this task type, only for 10 minutes”).

The three-plane design often has exceptions. For example, Aembit (mentioned above in the “Authentication” section can also authorize tool calls in the case of AI agents via the use of its context based MCP proxy.

Plane 3: Governance — “Know what exists, who owns it, and control lifecycle”

If Plane 1 is the front door and Plane 2 is the internal lock, Plane 3 is the map, the badge office, and the audit log.

Agentic AI pushes organizations into an identity reality where non-human identities outnumber human identities, show up in odd places (SaaS OAuth apps, service accounts, tokens, tool integrations), and are often created without clear ownership. Governance is the difference between “we think we have 200 agents” and “we can list every agent, its owner, its permissions, and how to shut it off.”

Astrix Security is explicitly framing itself around visibility and control for AI agents and NHIs—discovery, least-privilege guardrails, and “secure by design” deployment concepts. That’s governance language: inventory + risk + ownership + remediation. (Astrix Security)

Oasis Security positions as a Non-Human Identity Management platform focused on lifecycle management and governance across hybrid environments and AI identities—again, classic Plane 3 concerns: visibility, governance, and operational outcomes like reducing over-privileged access. (OASIS Security)

SailPoint is an incumbent governance giant, and their “Agent Identity Security” offering is explicitly about discovering, securing, and governing AI agents—very direct Plane 3 language, reinforced by their own documentation and product pages. (SailPoint Documentation)

Saviynt similarly frames non-human identity security around real-time inventory, posture, and unified visibility—again governance-first, even if it connects to enforcement capabilities in broader platform deployments. (Saviynt)

It’s also worth calling out that Okta and CyberArk can straddle into governance depending on which modules you deploy: Okta highlights ISPM for discovering identity sprawl and managing NHIs, while CyberArk emphasizes centralized discovery and governance for secrets/workload identities in its “Secure Secrets and Workloads” narrative. (Okta Docs)

Putting it together: the “where do these products fit?” answer in plain English

If you’re building an agentic security program and you’re holding this vendor list, here’s the clean mental model:

When you’re trying to answer “what is this agent and how does it authenticate safely without long-lived secrets?”, you’re in Plane 1: Aembit, CyberArk, and (increasingly for unified identity programs) Okta.

When you’re trying to answer “how do we enforce a task-scoped subset of privileges so an agent can’t roam?”, you’re in Plane 2: PlainID, Axiomatics, Styra/OPA, Cerbos, plus relationship systems like AuthZed/SpiceDB and Permit.io.

When you’re trying to answer “what agents/NHIs exist, who owns them, how do we review them, and how do we decommission them?”, you’re in Plane 3: Astrix, Oasis, SailPoint, Saviynt (and optionally Okta/CyberArk modules that provide visibility/governance).

Here is the figure to summarize what we have discussed so far.

The real punchline: a three-plane stack is how you make “hybrid delegation” safe

Agentic AI doesn’t create a single “identity crisis.” It creates a delegation crisis: agents act for humans, but operate as machines, and can be manipulated by untrusted inputs.

So the architecture has to reflect reality:

Authenticate the workload (Plane 1),

Authorize a subset of privileges bound to intent (Plane 2),

Govern the exploding estate of agents and NHIs (Plane 3).

Once you see the market through that lens, vendor evaluation gets simpler: you stop asking “who is the best AI security company?” and start asking “which plane is weakest in my stack—and which products actually strengthen that plane without pretending to replace the others?”

Thanks #Aembit for the support on this post.

Solid framing on the hybrid identity problem. The delegaton crisis angle is spot on, most teams treat agentic IAM like its just workload auth or just user delegation when its actually this weird blend that needs both layers. Ive been in environments where we tried to bolt on task-scoped permissions after the fact and it never worked cleanly, the three-plane seperation makes way more sense architecturally.

Thanks @Apurva Davé, and @Dan Kaplan from Aembit for co-author this article with me.